ECM Photon Liberation Law — Photon Liberation, Apparent-Mass Dynamics, and the Effective Transformation Coefficient aᵉᶠᶠ

This report presents a consolidated Extended Classical Mechanics (ECM) formulation for photon liberation from a gravitational well, with a corrected, sign-aware interpretation of the effective transformation coefficient aᵉᶠᶠ. The photon initially carries two equal energy components (inherent + interactional) forming the full apparent negative mass −2Mᵃᵖᵖ. As the photon climbs, interactional energy is expended linearly under a conserved liberation force F₀, producing a complementary evolution in frequency and wavelength that preserves c = f λ. The document defines aᵉᶠᶠ, derives the running relations for energy, frequency and apparent mass, demonstrates numerical examples, and outlines conceptual and cosmological implications.

1. Introduction

1.1 Motivation

Photons escaping gravitational wells show frequency shifts. ECM offers an alternative to curvature-based explanations by describing frequency change as a mass–energy bookkeeping process. This report corrects earlier misinterpretations of the quantity commonly labelled aᵉᶠᶠ and provides a consistent sign-aware framework for photons (negative apparent mass entities).

1.2 ECM postulates involved

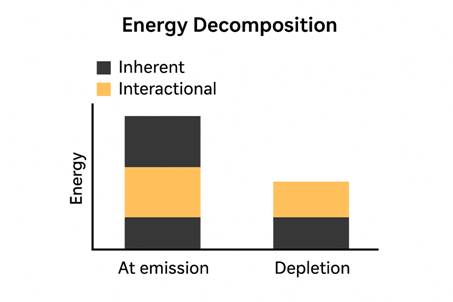

Energy Decomposition Principle. Any existent entity separates into inherent and interactional energy components.

Apparent mass mapping for photons. At emission the photon’s energetic state can be expressed as

E_emit = E_inh + E_int(0), with E_inh = ½ E_emit, E_int(0) = ½ E_emit

Manifestation principle. ECM identifies transformations between potential, kinetic and mass-energy via ΔPE_ecm ↔ ΔKE_ecm ↔ ΔM_m.

1.3 Purpose of this report

The goals are: define aᵉᶠᶠ unambiguously; derive the ECM photon liberation law with sign-awareness; demonstrate running relations and a worked numerical example; and discuss conceptual consequences for redshift and cosmology.

1.4 Interpretation of aᵉᶠᶠ and Photon Transformation Dynamics

This section summarises how a photon maintains constant propagation speed while its frequency and wavelength evolve under the action of a conserved interaction known in ECM as the liberation force. This interaction regulates internal mass–potential restructuring as the photon moves through gravitational fields and ensures that the relation c = fλ is preserved without invoking relativistic curvature or geometric interpretations.

i. Conserved Liberation Force

ECM views the photon as continuously undergoing internal transformation. The liberation force is the conserved interaction strength linking:

- the temporary mass-form associated with the photon, and

- the rate at which this mass-form undergoes transformation.

This force acts as an energy-transition regulator rather than a mechanical push. It maintains an internal balance that governs the photon's energy state at every point in its trajectory.

ii. Coordinated Adjustment of Frequency and Wavelength

Because the liberation force is conserved, a photon must adjust its frequency and wavelength in a perfectly complementary manner. When frequency increases, the wavelength shortens; when the frequency decreases, the wavelength lengthens. This complementary behaviour ensures that the propagation speed remains constant.

These changes occur because the liberation force regulates:

- how much mass-form is temporarily shifted inside the photon, and

- how quickly the transformation takes place.

iii. Internal Dependencies

Two internal relationships govern how the photon evolves:

- Transformation intensity: The liberation force strengthens when the transformation rate increases. A higher rate of internal restructuring corresponds to a stronger instantaneous shift in frequency and wavelength.

- Apparent-mass dependence: The transformation rate grows when the magnitude of the photon’s negative apparent mass increases. In stronger gravitational fields, this negative mass-form becomes larger, producing faster frequency rise and wavelength compression. In weaker fields, the photon approaches free-space behaviour.

Together, these dependencies explain frequency and wavelength variability within ECM without requiring relativistic curvature or geometric fields.

iv. Internal–External Correspondences

The photon’s observable behaviour maps directly onto ECM’s internal quantities:

- Frequency ↔ mass-form change: A rise or fall in frequency reflects a corresponding change in the photon's temporary mass-form.

- Wavelength ↔ transformation rate: Shorter wavelength indicates faster internal transformation.

- Constant speed ↔ conserved liberation force: The photon maintains constant speed because the interaction-force guiding its internal evolution never changes.

v. One-Sentence Summary

A photon preserves its constant speed because a conserved liberation force continuously balances internal mass-form transformation with complementary changes in frequency and wavelength, ensuring perfect dynamical symmetry as the photon moves through gravitational fields.

vi. Unified ECM Interpretation of aᵉᶠᶠ

In ECM, the quantity aᵉᶠᶠ is a generalized transformation parameter rather than a classical acceleration. For particles with real mass, it governs effective mass redistribution, potential-energy restructuring, and momentum exchange. The classical computation, used for geometry-driven motion, remains applicable across massive particles.

vii. aᵉᶠᶠ for Photon and Frequency-Governed Dynamics

For photons, whose behaviour is controlled by mass-potential transitions encoded in their frequency, the same parameter becomes the Effective Transformation Coefficient. At emission, the photon begins with a fixed value of aᵉᶠᶠ, but its subsequent propagation is regulated entirely by the conserved liberation force.

As the photon evolves, the symmetry between frequency, wavelength, and apparent-mass change ensures full consistency with the ECM kinetic-energy relation KEECM = ΔMₘ c² = hf. Thus, aᵉᶠᶠ unifies geometry-driven particle behaviour with frequency-driven photon dynamics within a single ECM framework.

2. Apparent Mass and Energy Decomposition

2.1 Inherent and interactional energy

At emission:

Corresponding apparent masses:

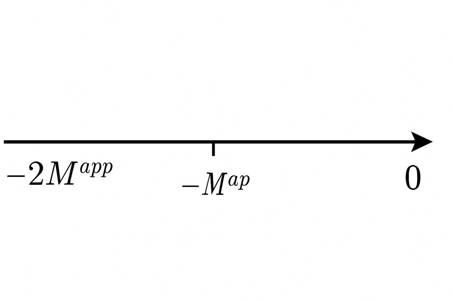

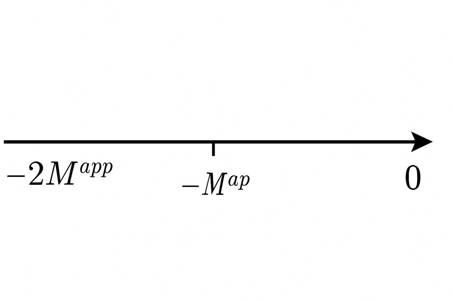

2.2 Negative apparent mass — number-line picture

On the number line the emission apparent mass sits most negative:

FIGURE 1. Number-line: −2Mᵃᵖᵖ → … → −Mᵃᵖᵖ → 0.

2.3 Energy pathway during ascent

The interactional energy decreases linearly with climb distance r under the conserved liberation force F₀:

3. Correct Definition and Interpretation of aᵉᶠᶠ

3.1 Why the classical view fails

Classical acceleration assumes positive inertial mass and a force that changes velocity. For photons—ECM negative-apparent-mass carriers—these assumptions fail. Therefore the quantity aᵉᶠᶠ must be reinterpreted.

3.2 ECM definition

Definition. aᵉᶠᶠ is the effective transformation coefficient that, together with apparent mass, enforces the conserved liberation force of the environment:

3.3 Behaviour near emission and far from the well

At emission: −2Mᵃᵖᵖ is most negative (largest magnitude); for photons this corresponds to the highest frequency and the shortest wavelength. Because λ is minimal at emission, the wavelength-change per unit distance is small → aᵉᶠᶠ is therefore smallest at emission.

As the photon climbs: the interactional portion is spent; −2Mᵃᵖᵖ becomes less negative (smaller magnitude), frequency decreases and wavelength grows, and aᵉᶠᶠ increases by the structural constraint to keep F₀ constant.

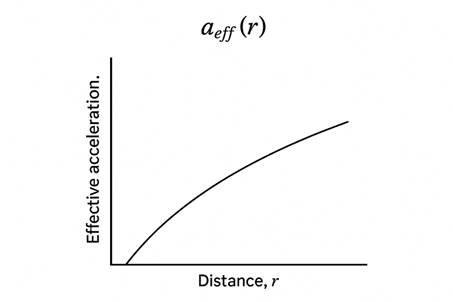

FIGURE 3. aᵉᶠᶠ(r) curve.

4. Photon Liberation Law

4.1 Structural constraint

The ECM photon liberation law is the conserved product:

4.2 Running relations

Interpretation: as E_ph decreases, f decreases, |−2Mᵃᵖᵖ| decreases and aᵉᶠᶠ increases — preserving F₀.

4.3 Preservation of the wave relation

Because E_ph = h f and λ = c / f, substituting yields

4.4 Maximum liberation distance

The interactional energy reaches zero at

At r ≥ r_max the photon retains only its inherent energy component (½ E_emit).

5. ECM Worked Example

Choose the example values:

5.1 Derived numeric values

5.2 Running-variable table (summary)

| Distance r | E_ph(r) | f(r) | λ(r) | −2Mᵃᵖᵖ(r) | aᵉᶠᶠ(r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.0×10⁻¹⁹ J | f(0) = E_emit/h | λ(0) = c/f(0) | most negative (largest magnitude) | minimum |

| r_max ≈ 7.5×10⁷ m | 2.0×10⁻¹⁹ J | f(r_max) = ½ E_emit/h | λ(r_max) = 2 × λ(0) | −Mᵃᵖᵖ (inherent) | maximum |

Note: the table is schematic; precise numeric columns can be calculated for intermediate r values if required.

6. Conceptual Consequences

6.1 Gravitational redshift as mass transition

ECM reads redshift as the depletion of interactional mass-energy rather than geometric stretching of spacetime. Photon frequency loss is therefore an energy bookkeeping process.

6.2 Photon-based timekeeping

Devices relying on photon frequency measure energy-state transitions. ECM predicts clock signals will reflect local interactional energy depletion.

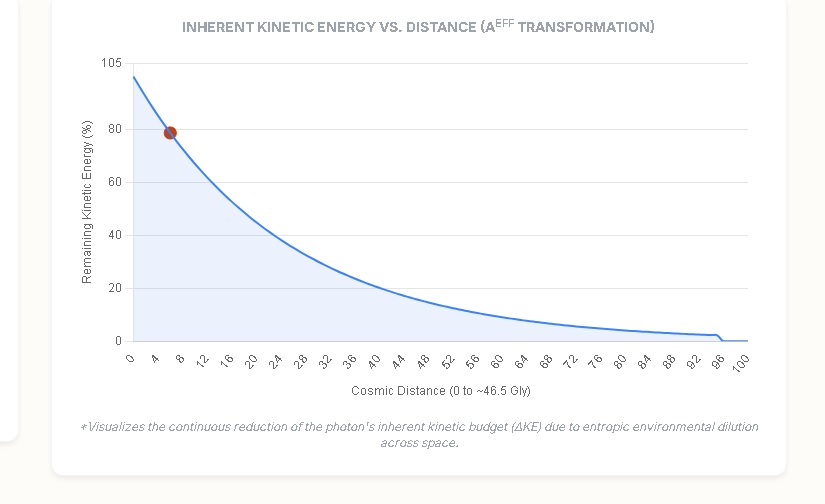

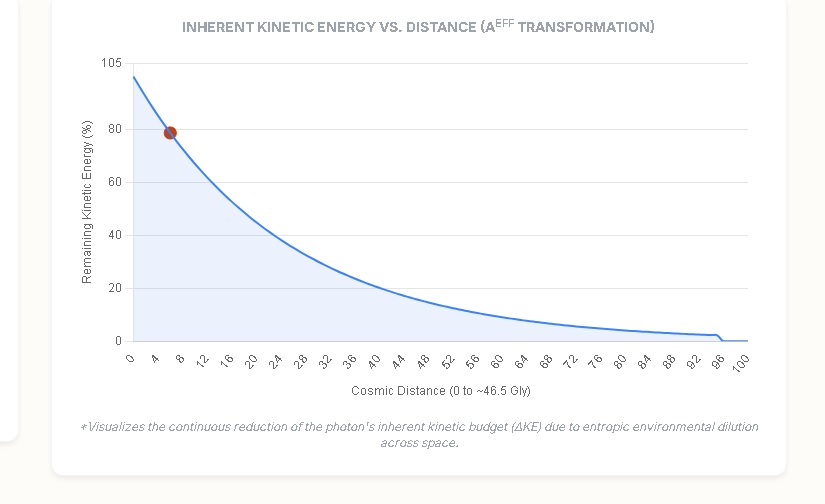

6.3 Cosmological implications

Cosmological redshift can be reinterpreted as progressive mass–energy dilution across cosmological propagation distances, connected to ECM entropy-driven time evolution.

7. Figures (to include)

- Number-line illustration of negative apparent mass: −2Mᵃᵖᵖ → −Mᵃᵖᵖ → 0.

- Energy-decomposition bar chart (inherent + interactional at emission, then depletion).

- Plot: aᵉᶠᶠ(r) vs distance (r), showing monotonic rise).

- Table/CSV for running values and a plotted version.

- Diagram: photon liberation in gravitational well (schematic).

- Plot: f(r) decreasing and λ(r) increasing as mirror curves.

Supplementary Notes on Figures and Extended ECM Conclusions

Figure 1 — Number-Line: Negative Apparent Mass Transition

Figure 1. ECM number-line representation of negative apparent mass. The photon begins at the maximum inherent interactional condition −2Mᵃᵖᵖ at emission, moves through the intermediate −Mᵃᵖᵖ inherent state, and approaches the zero-interaction limit as energy depletion completes. This visualises the ECM manifestation principle ΔPEᴇᴄᴍ ↔ ΔKEᴇᴄᴍ ↔ ΔMᴍ.

Figure 2 — Energy Decomposition at Emission and Along r

Figure 2. ECM energy-decomposition bar representation showing the inherent energy component and the interactional depletion component. At emission, E_emit = E_inherent + E_interactional. With increasing r, the interactional component decreases linearly via E_ph(r) = E_emit − F₀r, reflected directly in f(r), λ(r), and Mᵃᵖᵖ(r).

Figure 3 — Monotonic Rise of aᵉᶠᶠ(r)

Figure 3. ECM monotonic-increase behavior of aᵉᶠᶠ(r) as E_ph(r) decreases. Since aᵉᶠᶠ(r) = F₀c² / E_ph(r), the effective transformation coefficient rises continuously until the interactional energy is fully exhausted at −Mᵃᵖᵖ.

Figure 4 — Running Values Table and Plot

4.5 Running Values Table and Plot

The table below provides discrete running values of photon energy E_ph(r), frequency f(r), wavelength λ(r), apparent mass −2Mᵃᵖᵖ(r), and effective transformation coefficient aᵉᶠᶠ(r) for selected distances r from the emission point. A downloadable CSV is provided for detailed numerical analysis.

| Distance r (m) | E_ph(r) (J) | f(r) (Hz) | λ(r) (m) | −2Mᵃᵖᵖ(r) (kg) | aᵉᶠᶠ(r) (m/s²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.0×10⁻¹⁹ | f₀ = E_emit/h | λ₀ = c/f₀ | −2Mᵃᵖᵖ (max magnitude) | aᵉᶠᶠ min |

| 1.88×10⁷ | 3.0×10⁻¹⁹ | f₁ = 0.75 E_emit/h | λ₁ = 4c/3 E_emit | −1.5 Mᵃᵖᵖ | intermediate |

| 3.75×10⁷ | 2.5×10⁻¹⁹ | f₂ = 0.625 E_emit/h | λ₂ = 1.6 λ₀ | −1.25 Mᵃᵖᵖ | intermediate |

| 7.5×10⁷ | 2.0×10⁻¹⁹ | f_max = 0.5 E_emit/h | λ_max = 2 λ₀ | −Mᵃᵖᵖ (inherent) | aᵉᶠᶠ max |

Plotted Version

Note: The plotted aᵉᶠᶠ values are illustrative; precise numeric evaluation requires the running E_ph(r) via ECM equations.

4.6 Full Running Table and Plot (100 steps)

The following CSV contains 100 steps from r = 0 → r_max for ECM photon liberation values.

Note: Values computed using ECM running equations for photon liberation.

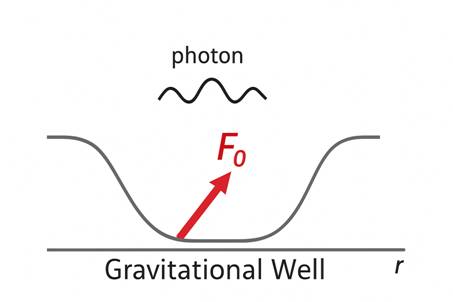

Figure 5 — Photon Liberation in Gravitational Well

Figure 5. Schematic representation of photon liberation from the gravitational well, showing inherent gravitational-interactional energy bound at emission and progressive release following E_ph(r) = E_emit − F₀r. This diagram complements Figures 1–4 by showing the physical geometry underlying ECM's mass-form and energy-form transitions.

Figure 6 — Mirror Curves: f(r) ↓ and λ(r) ↑

Figure 6. ECM mirror-curve behaviour: f(r) decreases monotonically as λ(r) increases, forming a symmetric pair of transformation curves governed by the depletion law E_ph(r) = E_emit − F₀r. This final version replaces the placeholder “6-mirror-curves.jpg” with the actual image aeff_ransformation.jpg.

Extended ECM Conclusions

The figures establish a consistent and unified extended description of photon behaviour within ECM. They clarify how frequency f(r), wavelength λ(r), apparent-mass Mᵃᵖᵖ, and mass-transition ΔMᴍ evolve under a gravitational interaction governed by the ECM manifestation principle: ΔPEᴇᴄᴍ ↔ ΔMᴍ ↔ ΔKEᴇᴄᴍ.

1. Approach Phase: r → rapproach → rmiddle

As a photon with emission frequency f₀ approaches the gravitational well, negative potential-energy contribution transforms into mass-form: −ΔPEᴇᴄᴍ → +ΔMᴍ, causing a blue-shift. The gravitational interaction strengthens toward rmiddle, producing the maximum frequency rise and maximum compression of the wavelength λ.

2. Centre Crossing: rmiddle

At the midpoint of the gravitational well, the energy-density gradient peaks. This corresponds to the largest mass-transition ΔMᴍ, maximum interaction-induced frequency, and maximum magnitude of apparent mass Mᵃᵖᵖ. The transition is continuous and symmetric.

3. Receding Phase: rmiddle → rrecede

After passing the midpoint, the mass-form contribution reverses: +ΔMᴍ → −ΔPEᴇᴄᴍ, producing a red-shift. The magnitude of redshift peaks symmetrically near rmiddle on the exit side of the well. The frequency and wavelength gradually return toward their free-space values as the gravitational influence weakens.

4. Escape and Free-Space Reversion

When the photon moves sufficiently far beyond rrecede, both ΔMᴍ and the gravitational influence approach zero. The photon recovers its free-space behaviour, with no further shifts and no residual distortion.

5. ECM Dominance Transition: r vs rexternal

The intrinsic evolution of a photon is governed by its distance

r from its emission-source gravitational well.

However, if an external gravitational well is encountered, the governing

kernel becomes:

dominant well = max( |Ksource(r)| , |Kexternal(rexternal)| )

If |Kexternal| > |Ksource|, the photon’s behaviour is

immediately dominated by rexternal, overriding its

original r-governed evolution. This exactly matches the behaviour depicted in

Figure 5, where an external well determines the photon’s blue-shift /

red-shift transitions.

6. Symmetric Gravitational Interaction: No Lasting Trace

For a symmetric external gravitational encounter, the interaction obeys: ΔMᴍ(in) + ΔMᴍ(out) = 0. The photon experiences temporary blue-shift on approach and red-shift on exit with no net residual effect. Once outside the external well, the photon reverts entirely to its source-based r-governed evolution. The external interaction leaves no permanent imprint, consistent with reversibility of the ECM mass–energy transition cycle.

7. Consolidated ECM Statement

Photon frequency, wavelength, and ΔMᴍ evolution are governed solely by the dominant gravitational energy-density kernel along the photon’s path. Approaching a well produces blue-shift; receding produces red-shift; and symmetric encounters leave no residual effect. External gravitational wells temporarily override the photon’s intrinsic source-governed evolution, but do not alter its long-term behaviour once the photon exits their influence.

8. Appendices

Appendix A — Formal definition of aᵉᶠᶠ

Definition A.1 — The ECM effective transformation coefficient aᵉᶠᶠ is defined by the universal structural relation:

For positive-mass entities aᵉᶠᶠ reduces to ECM effective dynamical acceleration; for photons (negative apparent mass) it becomes an energy–frequency transformation coefficient. Sign rules: when M^{eff} < 0, a^{eff} remains positive and their product F₀ is the liberation force (positive scalar).

Appendix B — Mass–Frequency Mapping

The working conversion used in this report:

Appendix C — Structural forces in ECM

F₀ is an environmental parameter representing the constant liberation force imposed by the source/well; it is not a local gradient of a metric but an effective structural constraint that converts interactional energy into liberated energy over distance.

9. References & Further Reading

The following ECM appendices, supplements, and related research documents provide the theoretical foundations referenced throughout this page.

- Appendix A – Standard Mass Definitions in Extended Classical Mechanics (ECM). Link

- Appendix B – Alignment with Physical Dimensions and Interpretations of Standard Categorization of Energy Types in ECM. Link

- Appendix 3 – Fundamental Total Energy in Extended Classical Mechanics (ECM). Link

- Appendix D – Negative Apparent Mass and Mass Continuity in ECM. Link

- Annexure 5 – Temporal Modulation vs Temporal Scale Variation in ECM. Link

- Appendix 6 – Angular-Time Correspondence in ECM. Link

- Appendix 6: Supplement A Link

- Appendix 6: Supplement A2 Link

- Appendix 7 – ECM-Specific Framework for Photon Sourcing and Emission Pathways. Link

- Appendix 8 – Energetic Structures beyond Planck Threshold. Link

- Appendix 8: Supplement A Link

- Appendix 8: Supplement B Link

- Appendix 9 – ECM's Cosmic Genesis and Gravitational Descriptions. Link

- Appendix 10 – Pre-Universal Gravitational and Energetic Conditions. Link

- Appendix 11 – Mass Redistribution and the Fourfold Structure of Mass in ECM. Link

- Appendix 12 – Effective Acceleration and Gravitational Mediation in Reversible Mass-Energy Dynamics in ECM. Link

- Appendix 13 – Proportionality Consistency and Inertial Balance. Link

- Footnote – ECM Principle at Work. Link

- Annexure 14 – Structural Displacement, Gravitational Decoupling, and the Archimedean Analogy in ECM. Link

- Appendix 15 – Photon Inheritance and Electron-Based Energetic Redistribution via Gravitational Mediation in ECM. Link

- Appendix 15: Supplement A Link

- Appendix 16 – Cosmic Inflation and Expansion as a Function of Mass-Energy Redistribution in ECM. Link

- Appendix 16: Supplement 1 Link

- Appendix 17 – Internal Force Generation and Non-Decelerative Dynamics in ECM under Negative Apparent Mass Displacement. Link

- Appendix 18 – Photon Energy, Electromagnetic Quantization, and the ECM Distinction between Electromagnetic Energy and Electrical Power. Link

- Appendix 19 – Photon Mass and Momentum: ECM's Rebuttal of Relativistic Inconsistencies. Link

- Appendix 20 – Frequency Scaling and Energy Redistribution in ECM. Link

- Appendix 20 – Supplementary Link

- Appendix 21 – Planck Thresholds, Energy Quantization Limits, and Nonlinear Collapse in ECM. Link

- Appendix 22 – Cosmological Boundary Formation and Mass-Energy Reconfiguration in ECM. Link

- Appendix 23 – Frequency-Origin of Energy, Photon Kinetics, and Mass Displacement in ECM. Link

- Appendix 24 – The Physical Primacy of Frequency over Time. Link

- Appendix 24: Supplement Link

- Appendix 25 – Apparent Mass Displacement and Energy-Mass Transitions of Electrons. Link

- Appendix 25: Supplementary 1 Link

- Appendix 25: Supplementary 2 Link

- Appendix 26 – (lost; pending recovery)

- Appendix 27 – Phase, Frequency, and the Nature of Time in ECM. Link

- Appendix 28 – Metrological Conflict Between Relativity and Time Standards. Link

- Appendix 29 – Cosmological Frequency Cycle and the Constructed Foundations of ECM Constants. Link

- Appendix 29: Supplementary 1 Link

- Appendix 29: Supplementary 2 Link

- Appendix 30 – Post-Latent Energetic Dynamics and the Dual-State Evolution of the Universe in ECM. Link

- Appendix 30: Supplementary 1 Link

- Appendix 31 – Frequency and Energy in Extended Classical Mechanics (ECM). Link

- Appendix 32 – Energy Density Structures in ECM. Link

- Appendix 33 – Gravitating Mass and Its Polarity in ECM. Link

- Appendix 34 – Scalar Mass Partitioning and Gravitational Phenomena beyond Relativity. Link

- Appendix 35 – (forthcoming)

- Appendix 36 – Entanglement as Ancestral Encoding — A Causal Resolution in ECM. Link

- Appendix 37 – Consistent Frequency-Energy-Radius Dynamics in ECM. Link

- Appendix 38 – Limitations of Relativistic Mass–Energy Equivalence Using Lorentz Factor γ. (forthcoming)

- Appendix 39 – Rebuttal to Misclassification of Sub-Light Electron Dynamics as Electromagnetic Phenomena. (forthcoming)

- Appendix 40 – Empirical Support for ECM Frequency-Governed Kinetic Energy via Thermionic Emission in CRT Systems. Link

- Appendix 41 – Gravitational Lensing as a Result of Field-Induced Photon Momentum Exchange in ECM. Link

- Supplementary 1 – Clarification Statement on the Kinetic Energy Form in ECM. DOI • Doc

- Appendix 42 – Unified Mechanism of Thermionic and Photoelectric Emission. Link

- Appendix 42 Part-2 – Unified ECM Framework of Atomic Vibration. Link

- Appendix 42 Part-3 – Evaluation of Refutations of Appendix 42 and 42-Part-2. Link

- Appendix 42 Part-4 – Dual Role of ΔMᴍ in Electron Confinement & Photon Interaction. Link

- Appendix 43 – Origin and Fundamental Energy in ECM. Link

- Appendix 43 Part-2 – Evolution of Quantum Theory and its Alignment with ECM. Link

- Appendix 44 – (forthcoming)

- Appendix 45 – The Artificial Mind of the Universe — ECM Perspective. Link

- Appendix 46 – ECM Elucidation: Newtonian vs Relativistic Curvature for Dark Energy. Link

- Appendix 47 – Variable Matter Mass in ECM. Link

- Appendix 48 – Clarification on the Kinetic Energy Expression in ECM — Integrating de Broglie & Planck Contributions.

- Appendix A, D, 7, 15 (Supp-A), 16, 25, 33, 46 – Common Part-2: ECM Foundations of Effective Mass, Negative Apparent Mass & Dark-Energy Analogies. Link

- Appendix 23 Part-2 – Frequency as More Fundamental than Mass in ECM. Link

- Appendix 49 – ECM Definitions of Time, Space, Velocity, Phase, Clock & Cosmic Distortion v1

- Appendix 12-II – Effective Acceleration vs Effective Transformation Coefficient in ECM. Link

- Appendix D2 – Negative Apparent Mass (NAM) and Its Foundational Derivation in ECM. Link